HKU Jockey Club Enterprise Sustainability Global Research Institute

World-Class Hub for Sustainability

John G. Matsusaka | Oguzhan Ozbas | Chong Shu | Irene Yi

The Regulation of Shareholder Democracy: Value Loss without Emissions Cuts

Feb 5, 2026

Key Takeaways

- Research Question: How did the SEC’s new regulations in 2021, enabling shareholders to more easily initiate environmental proposals, affect firms’ values and pollution emissions?

- Data and Method: The study measures stock price reactions to the 2021 Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Staff Legal Bulletin (SLB) 14L, which unexpectedly allowed more environmental proposals to go to a vote. The paper then tracks subsequent changes in corporate emissions, pledges, investments, and stakeholder engagement.

- Findings

- Firms with high levels of carbon emissions lost 1.6% in value (~$26 billion), concentrated among those that were previously targeted by environmental proposals.

- These same firms did not cut their actual or pledged carbon emissions or increase their clean investments in subsequent years.

- Managers of targeted firms increased their engagement with proponents (+6 pp) and stakeholders (+12 pp), suggesting the new regulation forced managers into activities that may have distracted them from ordinary business matters.

- Implications: Allowing more shareholder democracy on environmental issues can possibly erode firm value by distracting managers from their primary business responsibilities, without advancing environmental goals.

Source Publication:

John G. Matsusaka, Oguzhan Ozbas, Chong Shu, and Irene Yi (2025). The Regulation of Shareholder Democracy. SSRN Working Paper.

Background and Research Question

Shareholder democracy in the U.S. is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission. In particular, the SEC sets the rules concerning what sort of issues shareholders may propose for a vote, who can propose, and the processes for proposing. On November 3, 2021, the SEC changed the rules relating to environmental proposals by issuing Staff Legal Bulletin SLB 14L. This bulletin rescinded three previous bulletins that had allowed managers to block certain environmental proposals under Rule 14a-8(i)(7) and announced a new interpretation that made enabled shareholder activists to more easily make proposals related to social and environmental issues such as climate change.

SEC Rule 14a-8(i)(7), the “ordinary business” exclusion, allows companies to exclude shareholder proposals from their proxy statements if those proposals concern “ordinary business” matters. Companies argue the rule is necessary to prevent activists from meddling in complex day-to-day operational matters. Activists, on the other hand, have expressed concern that the rule is too subjective and can be used strategically by managers to exclude meritorious proposals.

This regulatory shift offers a natural experiment to examine how allowing shareholders to make more environmental proposals—in effect, expanding shareholder democracy—affects corporate value and policies. Specifically, did easing restrictions on climate-related proposals reduce firm carbon emissions and increase corporate costs?

Data and Method

The authors measure the impact of SLB 14L on firm value by analyzing the stock market reaction to the announcement on November 3, 2021. Carbon emissions data are drawn from the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (GHGRP); proposal and voting data come from FactSet and ISS Voting Analytics; financial data are taken from Compustat; and emissions pledges are obtained from the London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG). In addition, textual analysis of corporate proxy statements captures managerial engagement with proponents and stakeholders.

Findings and Discussion

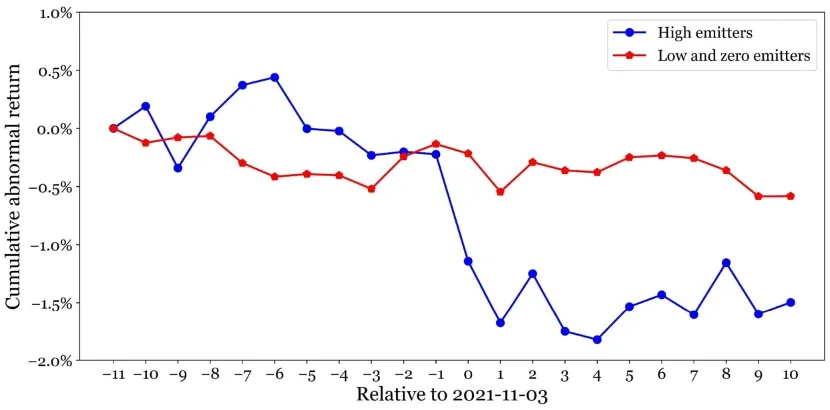

Following the announcement of SLB 14L, high-emitting firms experienced a statistically significant cumulative abnormal return of approximately –1.6% around the announcement date. Figure 1 shows the cumulative abnormal returns around the event date, revealing the clear divergence in consequences for polluting and nonpolluting firms. A related finding is that the effect concentrated among firms previously targeted by environmental proposals. This evidence implies investors expected the SLB 14L to reduce future corporate profits among high-emitting firms. The reason may be linked to an anticipated increase in the number of climate-related proposals and associated changes in firm policies. Firms with low or no carbon emissions were largely unaffected.

Figure 1. Daily CARs around the Release of SLB 14L

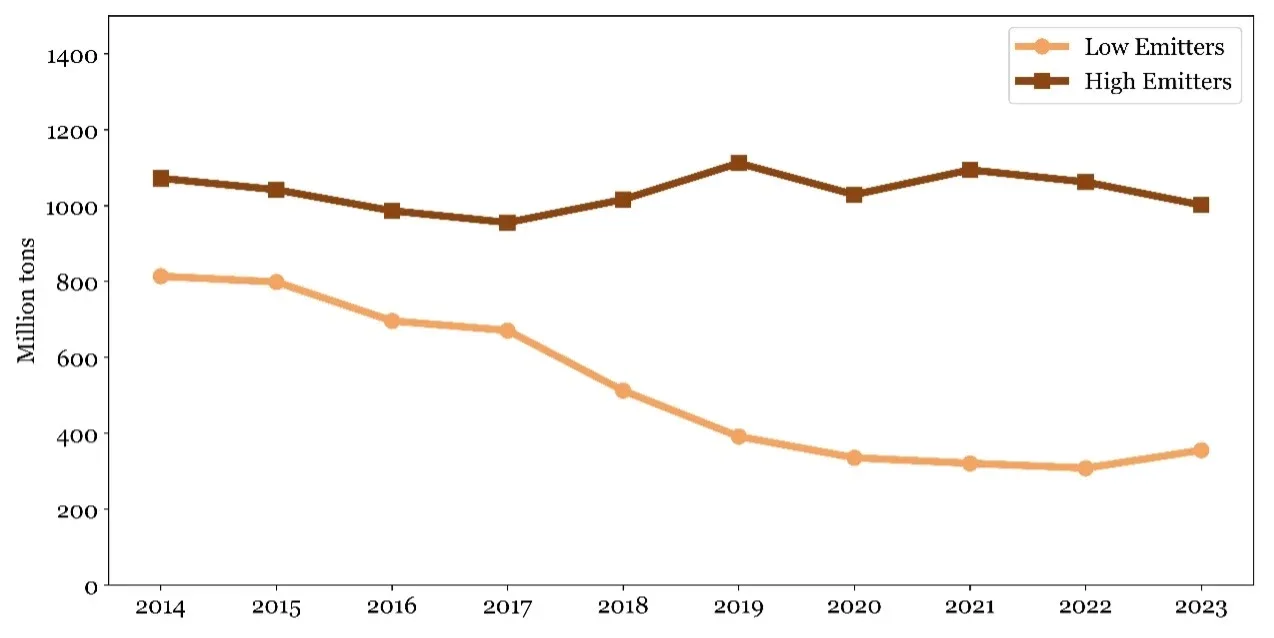

A natural interpretation of the evidence is that investors anticipated more climate-related proposals at the targeted companies that would force them to reduce emissions, thereby driving up their costs or causing them to forego profitable opportunities. To explore this interpretation, the study also examines changes in greenhouse gas emissions. Somewhat surprisingly, the authors find no evidence of significant changes in actual carbon emissions (see Figure 2), pledged carbon emissions, or capital expenditures, which might be a signal of new, cleaner technology. The SEC’s rule allowing more climate-related proposals had no detectable effect on greenhouse gas emissions.

Figure 2. Annual Greenhouse Gas Emissions

These two facts together present a puzzle: if high-emitting firms did not cut their emissions in response to SLB 14L, why did their expected profits fall? One explanation is that investors expected the anticipated higher volume of shareholder proposals to force managers to reallocate their attention toward engagement with stakeholders and proponents in an effort to prevent the passage of damaging proposals.

To test this explanation, the study searched for the text of corporate documents for statements indicating engagement with stakeholders. Engagement with stakeholders rose after the issuance of SLB 14L, especially for high-emitting firms. High emitters were 6 pp more likely to engage with proposal proponents and 12 pp more likely to engage with stakeholders than low emitters. This finding suggests the value loss in response to SLB 14L may have been due in part to “managerial distraction”: managers were expected to divert resources to administrative and relational activities rather than operational improvements.

Implications

The study has implications for shareholder democracy and for the SEC’s rulemaking process. In terms of shareholder democracy, the evidence suggests more may not always be better. When shareholder activists make proposals, managers often feel empowered to devote time and corporate resources to engaging with the proposal. If the benefit from a proposal is small, the distraction of managers can produce a net loss in value for the corporation. This result does not mean all shareholder democracy in general is value-reducing or that all shareholder proposals are harmful; rather, it suggests some forms of shareholder democracy may be better than others and calls for future research to determine the good and bad forms.

The study also raises questions about the SEC’s use of advisories such as SLB 14L. These advisories are not laws passed by Congress, nor official rules and regulations that must undergo the procedures established in the Administrative Procedure Act. They are non-binding advisories that the SEC itself explicitly states have “no legal force or effect.” The study shows that even though SLB 14L had no legal force or effect, market participants took it seriously, and it triggered a multi-billion-dollar loss in corporate value. As regulatory agencies become increasingly politicized, their ability to change regulatory practices suddenly and with few constraints increasingly exposes financial markets to political risk that has significant consequences on firm value and policies.