HKU Jockey Club Enterprise Sustainability Global Research Institute

World-Class Hub for Sustainability

Brandon Gipper | Carter Sampson | Shawn Shi

Do Firms Manipulate Their Carbon Emissions Reporting?

Feb 12, 2026

Key Takeaways

- Research Question: Do firms strategically underreport carbon emissions following firm-specific, high-profile climate controversies?

- Data and Method

- The study analyzes within-firm changes in carbon reporting behavior around 480 climate controversies from 2012–2021.

- Reported emissions are obtained from Trucost and compared with model-estimated emissions per Gipper, Sequeira, and Shi (2025) to capture underreporting.

- Findings

- Firms underreport emissions in the four years following a climate controversy.

- Consistent with intentional manipulation, firms underreport more when they avoid costly decarbonization, enjoy greater reporting discretion, and experience more stakeholder backlash.

- Following controversies, firms increase their use of third-party assurance, which does not reduce subsequent underreporting unless accompanied by board oversight.

- In an alternative setting involving mergers, acquisitions, and divestments, firms selectively apply carbon accounting rules to restate historical emissions in ways that create favorable trends.

- Implications: As mandatory and voluntary carbon disclosure proliferates, regulators and investors must look beyond innocent mistakes to intentional manipulation when allocating ESG capital and pricing carbon risk.

Source Publication:

Gipper, B., Sampson, C., & Shi, S. X. (2025). Do Firms Manipulate Their Carbon Emissions Reporting? SSRN Working Paper.

Background and Motivation

Carbon emissions disclosures play a central role in shaping decarbonization efforts and climate-related capital allocation. Prior research and media coverage document widespread inaccuracies in these disclosures, often explained as growing pains as firms learn how to measure emissions. Our evidence suggests these errors are not always benign. Using a large sample of firms, we find patterns consistent with intentional underreporting of direct emissions following climate-related controversies.

Reporting direct emissions involves substantial managerial discretion, including how firms define organizational boundaries and choose activity data and emissions factors. When a high-profile climate controversy puts a firm’s emissions under the spotlight, managers face strong incentives to use this discretion to lower the reported numbers. We therefore hypothesize that firms deliberately underreport their direct emissions after firm-specific climate controversies.

Data and Empirical Strategy

The analysis uses a panel of 896 unique public firms, comprising 5,370 firm-year observations from 2012–2021. Climate controversies are identified using RepRisk, focusing on severe, high-profile, firm-specific incidents related to atmospheric pollution that attract substantial media and stakeholder attention. Emissions data are obtained from Trucost, whereas CDP disclosures provide granular information on reporting practices, organizational boundaries, assurance, and governance.

We detect underreporting by comparing reported emissions with a model-predicted benchmark of “expected” emissions based on observable production characteristics, drawing on engineering research documenting that emissions scale with production output and technology. We measure underreporting as the numerical difference between disclosed and expected emissions.

Findings

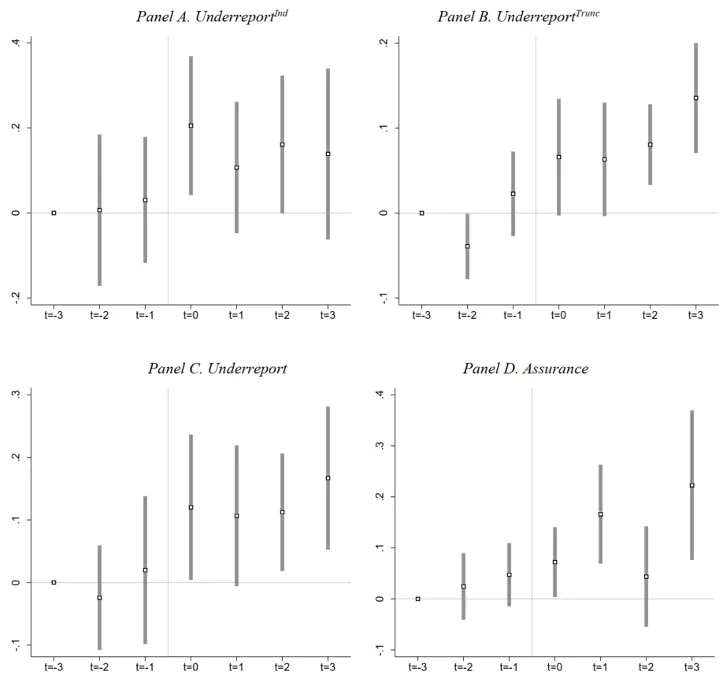

In the four years after a high-profile controversy, firms are significantly more likely to underreport their direct emissions and to do so to a greater degree. This pattern is specific to climate-related events: comparable social or non-carbon environmental controversies do not trigger similar reporting responses, reinforcing the interpretation that underreporting is a targeted reaction to climate-specific scrutiny. Event-time analysis shows little evidence of underreporting prior to a controversy, followed by higher underreporting afterward.

Figure 1. Event-Time Analysis

Note: This figure reports underreporting and assurance adoption around climate controversies in event time. For each year in the sample, firms experiencing a controversy in that year are designated as treated firms, whereas firms without any climate controversies during the sample period serve as control firms. The controversy year is denoted as t=0. All coefficients are measured relative to year 𝑡=-3. Coefficient estimates (dots), along with 90% confidence intervals (bars), are shown for each year.

We perform a battery of tests to distinguish emissions underreporting from genuine decarbonization and to link it to accounting manipulation. We find clear substitution between real emissions reduction and misreporting: underreporting is concentrated among firms that do not undertake costly operational responses—such as divesting polluting assets, investing in cleaner technologies, or developing green patents—suggesting managers view manipulation as a low-cost alternative when facing reputational and market pressure.

Underreporting is also more pronounced when firms have greater opportunity and discretion. It is strongest among firms with complex subsidiary structures, substantial non-controlling interests, and heavier reliance on estimated rather than directly measured emissions, features that make misreporting easier to implement and harder to detect.

Incentives play a central role. Underreporting increases following severe, widely disseminated, and firm-specific climate controversies, but not after less salient events. Reputational concerns appear to dominate contractual incentives in shaping these reporting decisions.

How do firms convince stakeholders their underreported numbers are credible? A natural mechanism is third-party carbon assurance, which prior research argues can serve as a voluntary signal of reporting credibility and commitment to sustainability. We find firms become more likely to obtain carbon assurance after controversies, but such assurance does not constrain underreporting unless supplemented with board oversight.

Finally, using a separate setting, we provide more evidence of how managers misreport. The GHG Protocol requires reported emissions to be benchmarked against previous years so that stakeholders can track a firm’s emissions over time. Historical emissions need to be restated after organizational boundary changes such as M&A or divestitures. We document that the same firm is more likely to restate historical emissions in years with mergers and less likely to restate historical emissions in years with divestitures, consistent with asymmetric carbon accounting to present more favorable historical emissions trends to stakeholders.