HKU Jockey Club Enterprise Sustainability Global Research Institute

World-Class Hub for Sustainability

Zoey Yiyuan Zhou | Douglas Almond

Biodiversity Co-Benefits in Carbon Markets? Evidence from Voluntary Offset Projects

Dec 11, 2025

Key Takeaways

- Research Question: This study evaluates whether voluntary carbon market (VCM) projects systematically deliver biodiversity co-benefits alongside carbon sequestration.

- Data and Method: A global, geocoded dataset of nature-based voluntary carbon offset projects (2000–2023) is analyzed using an event-study framework linking project boundaries to spatial measures of human pressure, ecological resilience, biodiversity integrity, and land-use change. The Human Influence Index (HII) is the primary measure of habitat condition because it integrates multiple sources of human pressure—such as land use, infrastructure, and population density—providing a globally consistent proxy for how ecosystems experience disturbance. Because habitat loss and degradation are the dominant drivers of biodiversity decline, HII directly captures the pressures most relevant to ecosystem integrity and habitat quality.

- Findings:

- Implementation of VCM projects is associated with a statistically significant 3.7% increase in human pressure (HII), indicating higher anthropogenic stress within project areas.

- Increases in HII occur regardless of stated biodiversity claims, protected area overlap, or certification status, suggesting a structural performance gap.

- Projects frequently accelerate conversion of biodiverse shrublands and certain forest types into pastures, revealing a trade-off between carbon storage objectives and ecological integrity.

- Implication: Current voluntary carbon market practices reveal systemic ecological risks and information frictions, underscoring the need for stronger safeguards, quantitative habitat monitoring, and transparency.

Source Publication:

Zhou, Z. Y., & Almond, D. (2025). Biodiversity Co-Benefits in Carbon Markets? Evidence from Voluntary Offset Projects. Review of Finance, rfaf066.

Background and Research Question

Global biodiversity continues to decline at unprecedented rates, yet policy mechanisms for conservation remain fragmented and largely ineffective. In this context, voluntary carbon markets have emerged as a prominent vehicle for channeling private capital into nature-based climate solutions. Developers frequently frame projects as “win-win” initiatives, promising simultaneous gains for carbon sequestration and biodiversity protection. Yet, despite their widespread adoption, systematic evidence evaluating whether these biodiversity co-benefits are realized has been conspicuously absent.

This study addresses this gap, asking whether voluntary carbon offset projects improve habitat quality in practice, and whether advertised biodiversity benefits align with measurable ecological outcomes. By examining approximately 2,700 geocoded nature-based VCM projects implemented between 2000 and 2023, the study investigates whether carbon-focused land management supports or undermines ecological integrity.

Data and Methodology

The analysis relies on high-resolution satellite-derived metrics, linking project boundaries to the HII, which quantifies cumulative anthropogenic pressure, including population density, infrastructure, and land-use intensity. HII values range from 0 (pristine) to 64 (maximal pressure), providing a direct measure of habitat degradation relevant for assessing biodiversity outcomes.

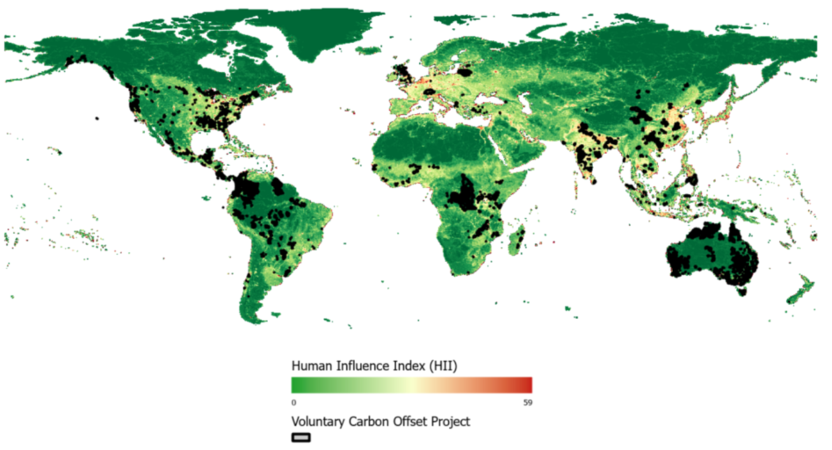

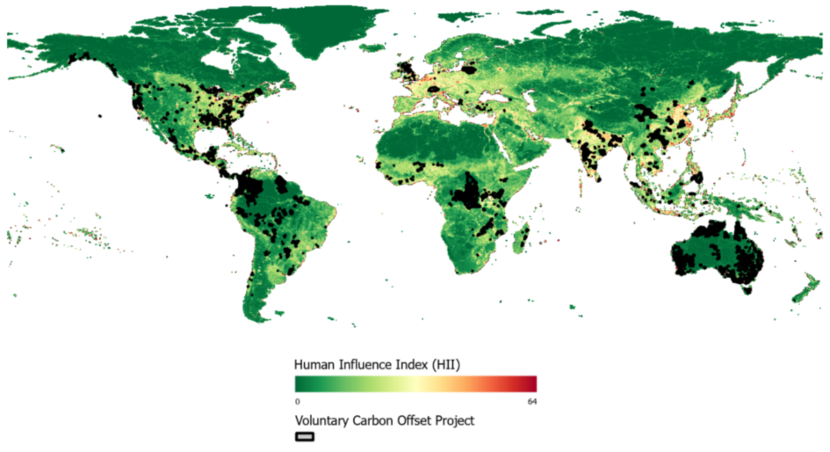

Figure 1. Carbon Offset Projects and Human Influence Index (HII)

Panel A: Human Influence Index in 2001

Panel B: Human Influence Index in 2020

Note: This figure presents the HII overlaid with the spatial boundaries of all voluntary carbon offset projects included in the full sample over the period 2000–2020. The HII quantifies cumulative human pressure on terrestrial ecosystems. Polygons delineate the boundaries of all projects registered in the dataset—irrespective of their establishment year or operational status—and are displayed consistently across both panels. Panel A corresponds to the global HII map for 2001, and Panel B corresponds to 2020, allowing visual comparison of human influence across time within the same spatial extent.

The primary identification strategy employs an interrupted time-series design with project fixed effects, capturing within-project temporal variation while controlling for unobserved, time-invariant project characteristics. Pre-implementation trends in HII are stable, supporting a causal interpretation of post-project changes. Robustness checks incorporate Bioclimate Ecosystem Resilience Index (BERI) and Biodiversity Habitat Index (BHI) as complementary measures of ecological condition, as well as satellite-based Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) data to examine systematic landscape transformations.

Findings

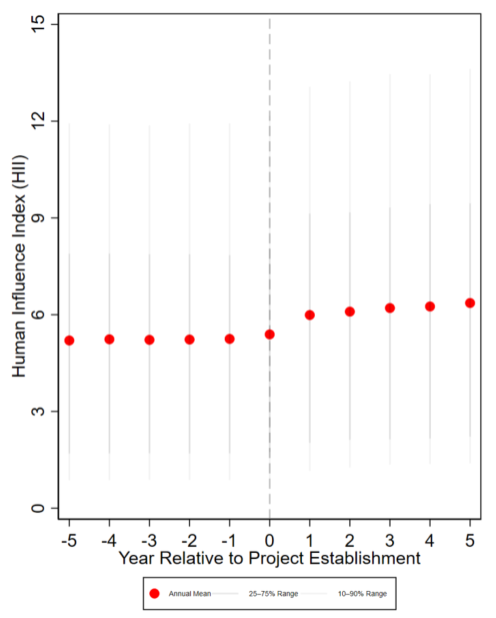

Contrary to the anticipated co-benefits, the establishment of voluntary carbon offset projects is associated with systematic increases in human pressure. Project implementation corresponds to a 0.187-point rise in HII, equivalent to a 3.7% increase relative to the sample mean, with logarithmic models suggesting an approximate 5% increase. Event-study analyses reveal flat pre-project trends and immediate post-project shifts in HII, peaking approximately three years after project initiation, indicating habitat degradation accumulates gradually rather than as a transient effect.

Figure 2. Biodiversity Impact of Carbon Offsetting Projects

Note: This figure presents the unadjusted relationship between carbon offset projects and biodiversity, measured using the HII, for the full sample of projects over the period 2000–2020. Estimates are based on a balanced panel spanning five years before and after project establishment (i.e., t-5 to t + 5). The x-axis shows years relative to establishment, and the y-axis shows mean HII values (higher values indicate greater human impact). Markers denote average annual HII. Lines represent the 25%–75% (dark) and 10%–90% (light) percentile ranges. The vertical dashed line at t = 0 marks project establishment. The joint F-test of the null hypothesis that all pre-treatment coefficients are equal to zero yields p = 0.999. A linear OLS fit over the pre-treatment period estimates a slope of 0.009 (p = 0.132).

Land-use analysis identifies ecosystem simplification as the principal mechanism. Projects systematically convert biodiverse shrublands and certain forest types into pastures, averaging 45.9 hectares of new pasture annually, largely drawn from 35.4 hectares of shrubland and 4.6 hectares of other forest types. These transformations reduce structural and compositional diversity, highlighting a critical trade-off: while carbon is sequestered through managed land-use change, biodiversity objectives are undermined.

No subgroup of projects reliably delivers positive biodiversity outcomes. Increases in human pressure occur in low-HII areas, projects within formally protected regions, those claiming biodiversity co-benefits, and even projects subject to third-party certification. Alternative metrics corroborate these findings, with BERI and BHI declining 0.3%–1.1% and 0.1%–0.6%, respectively, reinforcing the conclusion that ecological underperformance is systemic rather than incidental.

Implications

These findings expose a structural disconnect between marketed ecological benefits and realized outcomes in voluntary carbon markets. For investors, carbon credits claiming biodiversity co-benefits carry unpriced ecological risk, and reliance on registry certification or self-reported claims provides limited assurance of habitat protection.

For policymakers, the evidence underscores the need to expand monitoring, reporting, and verification frameworks to include quantitative measures of habitat condition, ecosystem heterogeneity, and resilience. Satellite-derived metrics offer a scalable and objective approach to track ecological outcomes and inform evidence-based regulation.

The study further illuminates a fundamental ecological trade-off: carbon-focused land management practices can achieve climate objectives while degrading biodiversity, a dynamic obscured by conventional carbon accounting. Achieving genuine “win-win” outcomes requires rigorous safeguards, transparency, and governance structures that explicitly align financial incentives with ecological integrity.