HKU Jockey Club Enterprise Sustainability Global Research Institute

World-Class Hub for Sustainability

Franklin Allen | Adelina Barbalau | Federica Zeni

Reducing Carbon Using Regulatory and Financial Market Tools

Jan 5, 2025

Key Takeaways

- This study develops a theoretical framework to explore how carbon taxes and financial market tools (e.g., sustainability-linked loans and bonds) interact in reducing carbon emissions.

- Carbon taxes remain the most effective tool for achieving emission reductions and increasing welfare but are often politically constrained.

- Carbon-contingent financing provides an alternative incentive for standard agents to adopt green technologies, but its effectiveness depends on the financial resources of environmentally motivated agents who are funding the transition.

- Although carbon taxes and market-based solutions can coexist, carbon-contingent financing may undermine political support for taxes, potentially reducing their overall effectiveness in addressing emissions.

- The model’s predictions emphasize the need for a balanced climate strategy, whereby carbon taxes and financial market solutions complement each other by targeting different regions or sectors with distinct characteristics.

Source Publication:

Franklin Allen, Adelina Barbalau, and Federica Zeni, “Reducing Carbon using Regulatory and Financial Market Tools,” SSRN Working Paper, February 2024.

The Climate Policy Dilemma

Addressing carbon emissions remain one of the most urgent global challenges. Traditional solutions, such as carbon taxes, aim to internalize the societal costs of pollution by assigning a price to emissions. However, these regulatory tools often face significant political hurdles, with opposition from industries and voters undermining their implementation.

In response, financial markets have introduced carbon-contingent instruments, such as sustainability-linked loans and bonds, offering private-sector mechanisms to incentivize green investments. This study investigates how taxation and financial markets interact, whether they can serve as substitutes or complements, and how their combined use impacts emissions, welfare, and political support for climate policy.

The Framework: Taxes Meet Markets

The study utilizes a theoretical framework to explore how regulatory taxation and financial market–based solutions interact in mitigating carbon emissions. Central to the model are two types of economic agents—standard agents and environmentally motivated agents—whose investment decisions determine the balance between polluting and non-polluting technologies.

Standard agents prioritize financial returns and are drawn to polluting technologies in a laissez-faire economy, due to their higher profitability despite environmental costs. By contrast, environmentally motivated agents internalize the societal harm caused by emissions and opt to invest in green technologies that eliminate emissions but yield lower economic returns.

In this framework, a carbon tax functions as a direct regulatory tool, pricing emissions to reflect their societal cost. By making pollution more expensive, taxes encourage standard agents to adopt green technologies, aligning private incentives with public goals. However, political feasibility depends on voter preferences, particularly those of the median voter, who determines the viability of implementing a carbon tax.

Alternatively, carbon-contingent financing provides a market-based pathway for reducing emissions. In this mechanism, environmentally motivated agents lend funds to standard agents under contracts tied to emission reductions, effectively subsidizing green investments. This private-sector approach circumvents political constraints but relies heavily on the financial capacity of environmental agents.

To account for real-world complexities, the model is extended to include agents with heterogeneous environmental preferences and technologies with convex abatement costs. This enhanced framework allows for a nuanced examination of how varying levels of taxation and market participation interact to shape emissions reductions, welfare outcomes, and political support for carbon pricing policies.

Key Findings: Balancing Trade-Offs

The baseline-model prediction confirms carbon taxes are the most effective mechanism for achieving optimal welfare and eliminating emissions—provided they are politically viable. By internalizing the social cost of carbon, taxes create strong incentives for the transition to non-polluting technologies. However, political constraints often make these policies unattainable.

In scenarios where carbon taxes are infeasible, carbon-contingent financing offers a practical alternative. When environmentally motivated agents have sufficient financial resources, these markets can replicate the welfare and emissions outcomes of an optimal tax without direct government intervention. However, when environmental funds are constrained, market-based solutions achieve only partial emissions reductions, leaving a significant share of polluting agents unchanged.

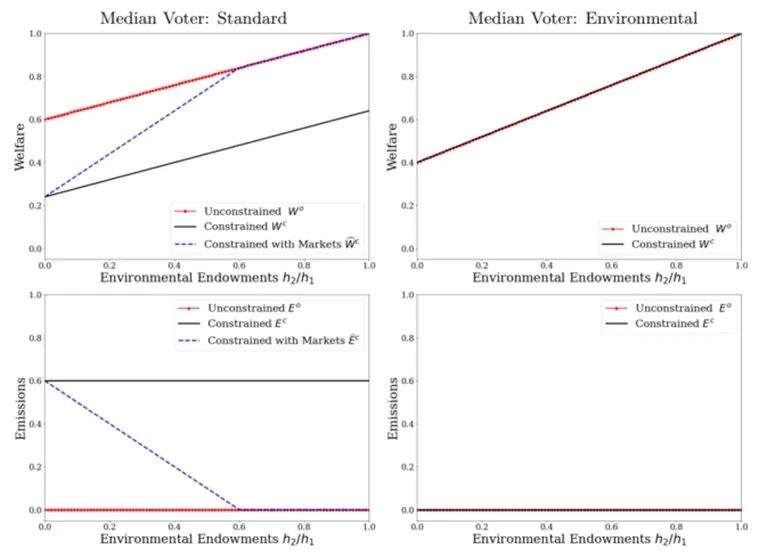

Figure 1. Reducing Carbon: Regulatory vs. Financial Market Tool (Baseline)

Note: The plots show the equilibrium welfare W (top plots) and emissions E (bottom plots) as a function of the relative endowments of environmental agents to the one of standard agents (h2/h1). The top plots refer to the case when the median voter is an environmental type (θ < 0.5). The bottom plots refer to the case when the median voter is a standard type (θ > 0.5). The blue line is welfare in the presence of financial markets. The black thick line is welfare with the politically constrained tax. The black dotted line is the reference welfare achieved from an unconstrained tax.

The interaction between carbon taxes and financial markets reveals complex trade-offs. Financial markets, while effective in facilitating emissions abatement, can undermine political support for taxation by offering private-sector alternatives. This reduced reliance on taxes diminishes their perceived necessity among voters, weakening political backing. In turn, the reduction in political support can lead to welfare losses, particularly in cases where tax revenues—and the rebates they fund—are crucial for maintaining public support, or where market-based abatement efforts fail to achieve the scale of reductions necessary to meet environmental targets.

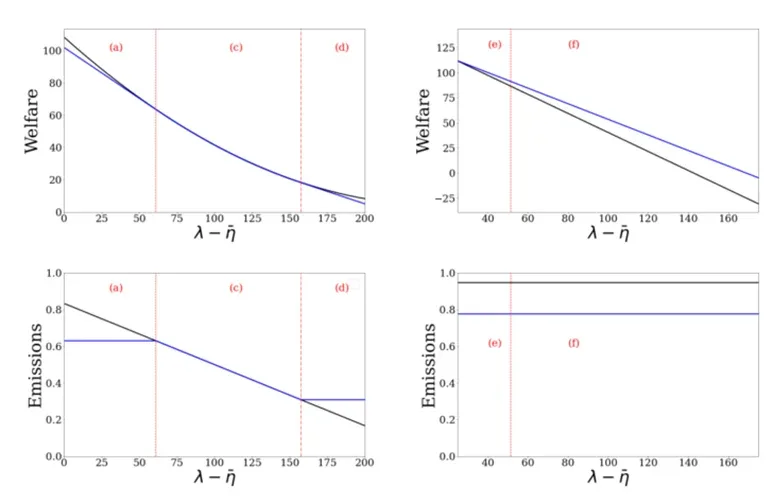

These dynamics are illustrated in Figure 2. The two graphs on the left show equilibrium welfare and carbon emissions with (blue line) and without (black line) financial markets. The outcomes under varying social costs of carbon are as follows: in a low social cost scenario (a), financial markets exceed the regulator’s efficient target, leading to lower welfare but higher emissions reductions than in the counterfactual economy. In a high social cost scenario (d), financial markets fall short of achieving the necessary abatement, and reduced political support for the tax makes the unconstrained tax unfeasible. In the intermediate range (c), financial markets yield outcomes similar to those in an economy without markets.

When the baseline economy does not support the implementation of a carbon tax, financial markets can offer a strictly better alternative, as shown in the top- and bottom-right plots of Figure 2. If financial markets achieve higher abatement than the constrained carbon tax, both welfare and emissions reductions improve, as seen in (e) and (f). However, if financial markets provide insufficient abatement, they exacerbate the political constraint without delivering adequate reductions, resulting in lower welfare and higher emissions than in the counterfactual economy without markets.

Figure 2. Reducing Carbon: Regulatory vs. Financial Market Tool (Extended)

Note: The y-axis represents equilibrium welfare (top plots) and emissions (bottom plots) in an economy with only a carbon tax (black line) versus one where both financial markets and the tax are present (blue line). The x-axis shows the unconstrained optimal benchmark tax (in $ per ton of carbon), which increases with the social cost of carbon parameter λ for a given distribution of preferences.

Implications: Crafting a Comprehensive Climate Strategy

Overall, the findings suggest carbon-contingent financing mechanisms, such as sustainability-linked loans and bonds, can serve as effective alternatives to carbon taxes in regions with limited political support for taxation. These instruments encourage the adoption of non-polluting technologies while bypassing the challenges of direct taxation. However, over-reliance on financial market solutions may weaken support for carbon taxes, as profitable alternatives reduce their perceived necessity, potentially leading to inefficiencies and higher emissions. To address this possibility, carbon-contingent funds should be directed toward unregulated sectors to avoid undermining political support for carbon taxes.

The interplay between regulatory and market-based tools underscores the need for a balanced climate strategy, whereby both carbon taxes and financial market solutions complement each other. Whereas carbon-contingent financing can address sectors where carbon taxes are politically unfeasible, well-designed carbon tax systems—coupled with transparent and equitable rebate schemes—can sustain public support and ensure broader policy acceptance.