HKU Jockey Club Enterprise Sustainability Global Research Institute

World-Class Hub for Sustainability

Heng Geng | Harald Hau | Roni Michaely | Binh Nguyen

Common Institutional Investors and Board Representation in Rival Firms?

Apr 7, 2025

Key Takeaways

- A priori, common board representation in competing firms is one of the most natural mechanisms to coordinate policies across firms.

- The study finds institutional board representation is unlikely to be the primary mechanism for investors to coordinate corporate decisions.

- Joint board representation in rival firms is uncommon, even among the largest asset managers (e.g., Vanguard, Blackrock).

- In fact, institutional investors’ direct presence on firms’ boards is generally rare.

Source Publication:

Geng, H., Hau, H., Michaely, R., & Nguyen, B. (2025). Common Institutional Investors and Board Representation in Rival Firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, Forthcoming.

Collusive Common Institutional Investors: What Are Channels of Influence?

Over the last two decades, the dramatic increase in ownership of institutional investors has raised questions about collusive corporate policies when ownership stakes in rival firms become substantial. However, how common shareholders across competing firms engage with and exert influence on corporate decision-making remains unclear. Regarding antitrust issues, judges and legal scholars generally agree the underlying channel through which the effect of common ownership manifests remains vague and disputed. The plausibility of this channel rests on a well-settled principle in U.S. corporate law: board directors are responsible for making all major corporate decisions. Given their considerable ownership stake in U.S. public firms, institutional shareholders could be widely represented in the boardrooms of U.S. public firms so that common institutional shareholders can coordinate rival firms through their board representatives. Despite the plausibility of this channel, little empirical research seeks to verify it. This paper aims to fill the gap.

Data

This study’s data come from two sources. First, the study gathers information on directors who are nominated by 13F institutional investors. Since 2004, the SEC requires all U.S. public companies to disclose shareholders involved in nominating directors. This information is collected from firms’ proxy statements (Form DEF 14A). Second, this study searches for directors who concurrently work for the firms’ institutional directors. Director employment information from BoardEx helps determine if directors have concurrent employment with any 13F investors who also hold shares in the firm where the director serves on the board. This thorough approach to identifying institutional directors sets the stage for subsequent analyses in this study.

Finding #1: Institutional Board Representation Is Surprisingly Rare.

Among a sample of 81,255 Compustat firm-years, only 6,292 (7.7%) have at least one institutional director representing an institutional shareholder owning more than 1% of outstanding shares. This number shrinks further to 3,286 firm-years (or 4.0%) when narrowing down to institutional shareholders owning over 5% of outstanding shares. This representation rate is rather low compared with the collective ownership of institutional investors. A significant 39.7% of these institutional directors are associated with bank-affiliated investment companies and another 37.6% with sophisticated investors (i.e., hedge funds, venture capital, and private equity firms). Unsurprisingly, activist shareholders account for a majority of the institutional directors in the sample. Yet, somewhat unexpectedly, directors tied to independent investment firms—including major entities such as Blackrock and Vanguard—make up only 16.2% of these directors.

Finding #2: Common Institutional Shareholders between Rival Firms Rarely Establish Joint Board Representation in Both Firms.

A crucial insight from this study is that while individual firms might prefer unbiased hiring and promotion policies, the labor market as a whole benefits from maintaining discrimination. Bias functions as an implicit collusion mechanism: by segmenting workers into separate career tracks, firms can reduce competition for top talent and suppress overall wage growth.

From a societal perspective, however, this outcome is inefficient. The segregation of firms based on biased promotion practices leads to misallocation of talent, reducing overall productivity and deepening inequality. Policies that promote transparency in promotion decisions and counteract subtle biases could therefore enhance labor market efficiency and worker welfare.

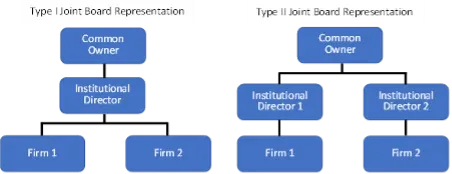

As illustrated in Figure 1, this study accounts for two types of joint board representation: Type I board representation, where one single institutional director represents the common shareholder on the boards of competing firms; and Type II representation, where separate individuals represent a single common shareholder. Of 2,986,115 competing firm pairs, where a block common shareholder owns over 1% of outstanding shares in both firms, only 269 (0.01%) pairs feature Type I joint board representation, and 852 (0.03%) pairs feature Type II joint board representation.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Debate on Common Ownership

The data do not support the assumption that institutional investors drive corporate coordination through board representation. To the extent that common owners help coordinate firms’ actions, other mechanisms—such as private engagements with management, shareholder voting, or indirect market signals—may be more relevant in understanding how institutional investors coordinate corporate strategies among rival firms.