HKU Jockey Club Enterprise Sustainability Global Research Institute

World-Class Hub for Sustainability

Markus Leippold|Zacharias Sautner|Tingyu Yu

Corporate Climate Lobbying

Nov 8, 2024

Key Takeaways

- While climate change requires regulatory action, a common concern is that more ambitious climate action, at least in part, is obstructed by firms’ lobbying activities.

- This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of firms’ climate lobbying activities and their impacts. Key findings include the following:

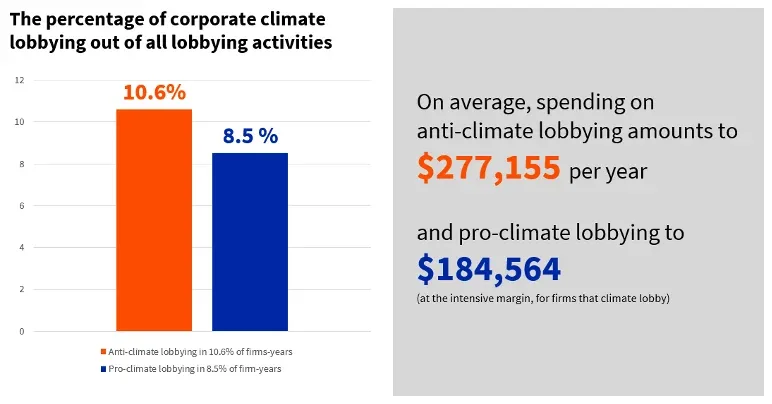

- US-listed firms spend on average $277,155 annually on anti-climate lobbying and $184,564 on pro-climate lobbying.

- Firms with higher carbon emissions and reliance on fossil fuels are more likely to engage in anti-climate lobbying, whereas firms with a focus on green innovation tend to support pro-climate lobbying.

- Firms that spend more on anti-climate lobbying earn higher returns, probably because of a risk premium.

- The stock prices of anti-climate lobbying firms are bid down around major events that increase investor beliefs about climate-related regulatory uncertainty, and vice versa.

- The findings on “camouflaged lobbying” and “lobbying through trade association” reveal a disconnect between what corporations are communicating to the public about net zero and their lobbying actions, highlighting the need for greater transparency.

Source Publication: Markus Leippold, Zacharias Sautner, Tingyu Yu. (2024). Corporate Climate Lobbying.

Background and Research Questions

Climate change demands regulatory action from governments, yet most countries’ climate efforts are insufficient. A common concern is that firms’ lobbying activities partly hinder more aggressive climate actions, as they seek to influence politicians or policymakers to undermine, delay, or avoid pro-climate regulations or policies. Despite this fact, our understanding of the scope, motivation, and impact of firms’ climate lobbying activities is limited. Leippold et al. (2024) address this gap with a comprehensive analysis, offering insights into the following aspects.

Data, Patterns, and Trends

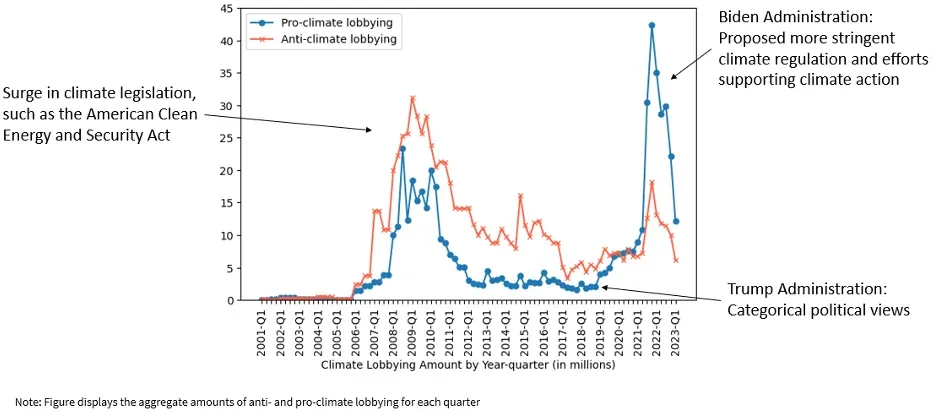

Drawing on data from OpenSecrets, this study analyzes climate lobbying activities by 4,055 US-listed firms over two decades, from Q1 2001 to Q1 2023. Among the 257,691 lobbying reports filed by sample companies, 26,714 address climate issues. Of these reports, 15,719 disclose a political affiliation: 8,161 align with the Republican Party (classified as anti-climate lobbying) and 7,558 align with the Democratic Party (pro-climate lobbying). On average, firms spend $277,155 annually on anti-climate lobbying, compared with $184,564 on pro-climate lobbying. Figure 2 illustrates climate lobbying trends over time, highlighting notable shifts in lobbying focus and expenditure across this period.

An intriguing finding from the data is the practice of “camouflaged lobbying” and “lobbying through trade associations.” “Camouflaged lobbying” refers to instances where firms intentionally avoid using explicit climate-related keywords in their reports. This tactic is particularly common among companies that have recently started lobbying on climate issues or those that have shifted their stance from anti- to pro-climate, likely as a strategy to align with stakeholder expectations while minimizing negative attention. “Lobbying through trade associations” refers to the practice of firms pooling resources through trade associations, which collectively advocate on behalf of industry interests. Both trends have raised concerns over the transparency of corporate climate lobbying practices.

Figure 1. Percentage and average spending of anti- and pro- climate lobbying

Figure 2. Spending on corporate climate lobbying over time

Navigating Risks and Opportunities through Lobbying

Corporates’ climate lobbying positions are often rooted in their business models and environmental footprints. This study analyzes the correlation between corporate climate lobbying intensity and proxies for climate-related risks and opportunities—specifically, carbon emissions and green innovation. It finds firms with high carbon emissions or a reliance on fossil fuels, such as those dependent on coal, oil, or natural gas for electricity generation, are more likely to lobby against climate policies. By contrast, companies that demonstrate a strong commitment to green innovation, as evidenced by factors such as green patents and discussions of environmental issues during earnings calls, tend to support pro-climate regulations. This alignment reflects these companies’ interests in a net-zero transition and signals their readiness to capitalize on the opportunities it offers.

Do Investors Care about Corporate Climate Lobbying?

Relating firms’ stock returns to their corporate climate lobbying expenses, the authors found firms engaging in anti-climate lobbying experienced higher stock returns in the period following 2010. This finding suggests investors may be seeking a premium for their investments, potentially compensating for risks associated with damaged trust in these firms or their slow progress in transitioning to sustainable practices, as they hope lobbying efforts will succeed.

To test this hypothesis, the authors analyze stock return reactions to two major climate-related policy events that unexpectedly shifted investor beliefs. The first event occurred when Senator Lindsey Graham, a Republican from South Carolina, withdrew his support for the Waxman-Markey Bill, formally known as the American Clean Energy and Security Act. This bill, which aimed to establish a national cap-and-trade system, was a critical proposal in US climate policy. It attracted intense interest across various sectors, prompting firms to engage lobbyists on a large scale. The second event was the announcement of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the most ambitious climate change legislation in US history. The IRA aims for a 41% reduction in emissions by 2030 relative to 2020 levels, raising uncertainty for firms reliant on fossil fuels, due to potential costly regulatory changes.

The results show the stock return dynamics surrounding these two climate policy events are consistent with the risk-premium hypothesis: stock prices of anti-climate lobbying firms were bid down (bid up) when the events increased (decreased) investor beliefs about climate-related regulatory uncertainty.

Implications

The comprehensive data analysis in this study, particularly the patterns of “camouflaged lobbying” and “lobbying through trade associations,” reveals a significant disconnect between what corporations communicate to the public about their net-zero commitments and the lobbying actions they undertake behind the scenes. Although many firms publicly express support for climate action, their lobbying activities, especially those related to anti-climate policies, often contradict these public statements. This misalignment not only undermines public trust but also raises concerns about the authenticity of corporate climate commitments.

Overall, the study emphasizes the growing need for greater transparency in corporate lobbying efforts. Investors, policymakers, and stakeholders must be able to critically assess whether companies are truly aligning their actions with their climate promises, as well as evaluate the associated risks. In the absence of transparency, corporate efforts to address climate change may be undermined by lobbying activities that seek to delay or block meaningful regulatory progress, ultimately impeding the transition to a net-zero economy.